One of the most important responsibilities of our schools is ensuring that our students become proficient readers and writers. That’s why KIPP is investing in a years-long initiative to improve K-2 literacy instruction across our schools. We’re leveraging a strong evidence-based approach and partnering with our communities to ensure all students become readers and writers.

Learning to read can be a challenge for students. That’s because reading is unnatural. Compare learning to read with learning to speak. If you’ve spent time with a baby or young child, you know that they absorb language, often picking up new words and phrases without any direct instruction or explanation. The human brain is wired to acquire oral language. In contrast, written language is a technology, and a recently created one at that! Whereas oral language developed about 100,000 years ago, written language was invented between 5,000 and 10,000 years ago by Chinese and Mediterranean cultures. These early written languages were for business and accounting purposes. The concept of an alphabet, which allowed for more nuanced communication of ideas, dates back just 5,000 years. Our brains are not inherently wired for written language—in fact, becoming literate involves re-wiring our brain.

Another challenge is the complexity of the English language. English has 26 letters that represent 44 phonemes—speech sounds—and more than 100 spelling patterns for those sounds. The English language is also influenced by other languages like Greek, Latin, and French in ways that affect word meaning and spelling patterns. Additionally, English has many regional and cultural dialects. That’s not to say that English is impossible to master—quite the opposite. About 86 percent of English follows a predictable and explainable spelling pattern. But it does add to the complexity!

Written language also differs quite a bit from spoken language. Written language tends to have more complex sentence structures than one would encounter in a conversation. Books also contain more academic vocabulary and/or less-frequently-used words. This puts an additional challenge on readers to make sense of words and sentence and text structures that don’t conform to how we typically speak to one another.

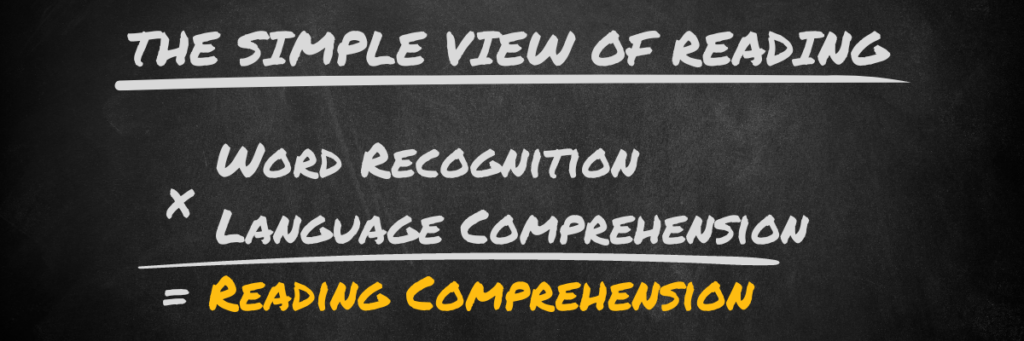

Despite these challenges, we know how to effectively teach students by following the science of reading. In fact, research tells us that with effective instruction, 95 percent of students will become skilled readers, including students with mild to moderate disabilities (Lyons, 1998; National Reading Panel, 2000; Moats, 2020). The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) is a foundational explanation of how we read. The Simple View of Reading is an equation: Word Recognition x Language Comprehension = Reading Comprehension.

In other words, in order for a child to become a proficient reader, we must teach them to recognize words accurately and quickly and we must teach them to understand language. The Reading Rope (Scarborough, 2001) builds upon the Simple View of Reading and identifies the specific skills within word recognition (e.g., phonological awareness) and language comprehension (e.g., vocabulary) that must be developed for a child to become a proficient reader. Both frameworks inform the way we teach students to read.

Students learn to recognize words automatically through intentional instruction. An effective early literacy curriculum follows a systematic scope and sequence, in which skills are introduced logically and in order of complexity. These skills are taught explicitly, meaning that the teacher provides an exemplar model, followed by guided practice and independent practice. Practice happens both out-of-context (e.g., reading individual words) and in-context (e.g., in a decodable reader) to maximize effectiveness.

Teaching students to read isn’t just about word recognition—we must also support their language comprehension. That means that teachers are intentionally building students’ content knowledge across diverse categories of topics. In grades K-2, this often happens through read-alouds and by providing students access to complex, grade-level texts. Students also need opportunities to discuss and write about the texts they are reading.

At KIPP, we are deeply committed to following evidence-based practices and equipping our teachers and leaders with the knowledge, skills, and tools to implement structured literacy. We know this is the most efficient and effective way to realize our vision that every child grows up free to create the future they want for themselves and their communities. In order to realize this vision, our schools are engaging in professional learning communities, in which they are building content knowledge and sharing best practices. Regions are also working toward implementing a common approach to assessment and adopting high-quality instructional materials. We promise families that all students will become strong readers, writers, and communicators so that they can learn, discover joy in reading, express themselves, and craft their future.

Author: Lindsay DeHartchuck – Director, Early Childhood and Elementary Literacy, KIPP Foundation

Learn more about KIPP’s approach to excellent teaching here.